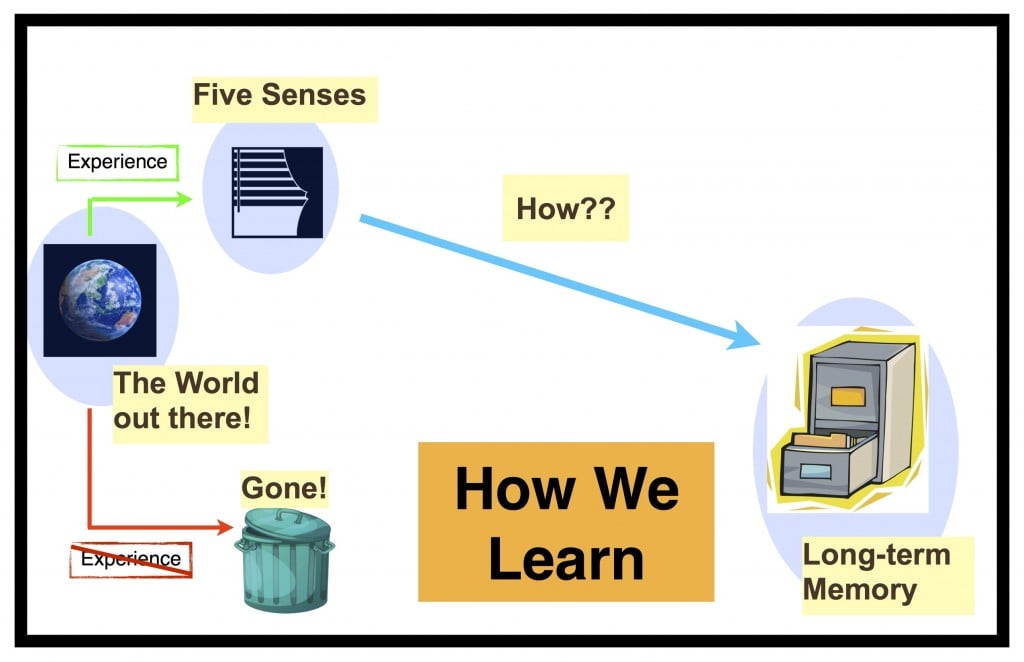

We began our exploration of immigration by beginning a “read aloud” of Shaun Tan’s wordless graphic novel, The Arrival. I told the kids that we were going to be studying the topic of immigration, which is the word social scientists give to the idea that people move from one place to another. That’s about all I told them, so far.

My goal has been to open up some ideas about immigration in a way that the kids could first feel the disorientation and reorientation of the immigrant, before we got into some more of the nitty-gritty aspects of the topic. I’m thinking, here, of how some experiences (war, famine, persecution, hope) pushed people to leave what they knew in the home country to begin a new life in a strange land, the different experiences that people endured along the way, the disorientation of the arrival, the power structure immigrants landed in, and, using whatever resources they possessed, the way immigrants tried to make a new home for themselves in their new land.

Ultimately, I want the kids to begin to understand how this powerful force in history shaped people and places. But I also hope the students might understand the immigrant’s story metaphorically, as the story of any journey into a new land. The immigrants’ disorientation and reorientation applies to many situations.

Maybe, as we read we might see our own lives, our own learning as a kind of immigration from once familiar territory into a new, barely understood land. At the very least, for rural Iowans whose immigrant identity is tenuous to vanishing, we might gain a better sense of our fellow citizens whose experience with home and belonging is so different than our own. Perhaps. Perhaps.

We gathered on the floor, in chairs, and around nearby tables while I projected the book from my iPad onto the screen.

We began to read and talk.

* * * * * * *

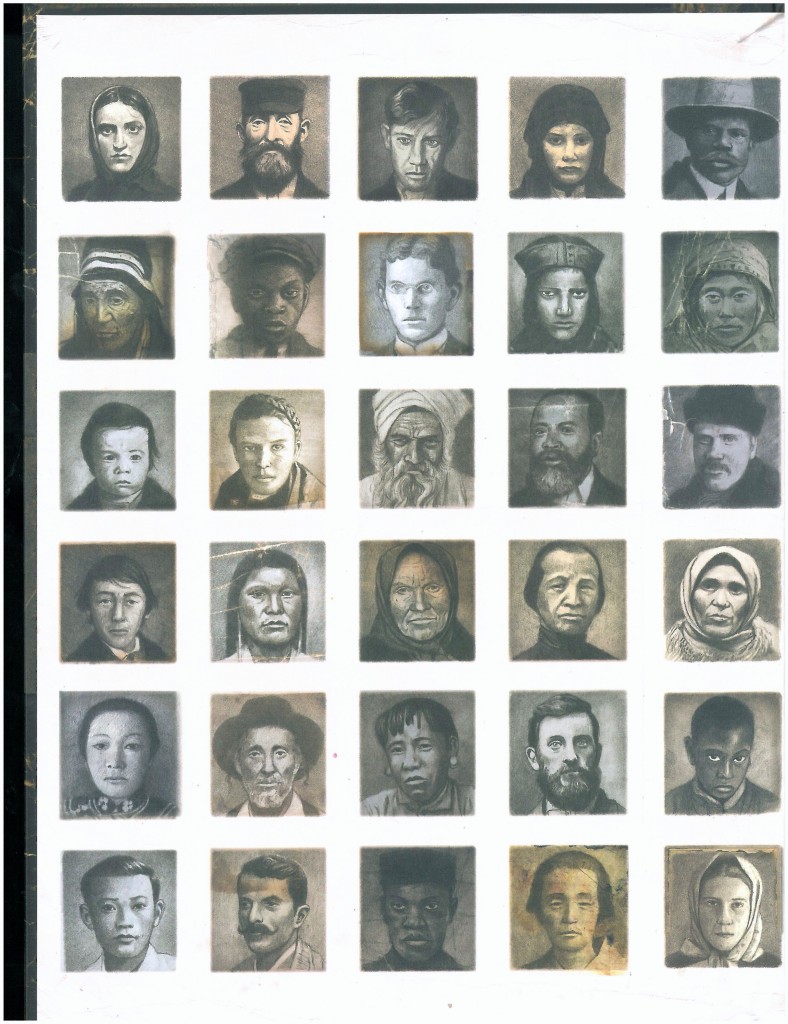

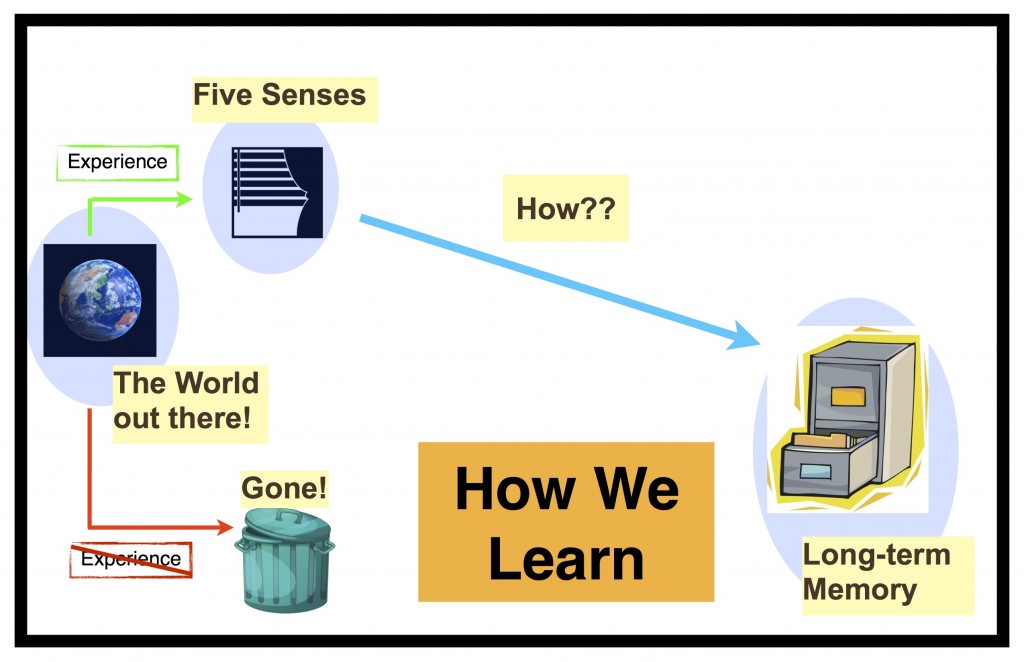

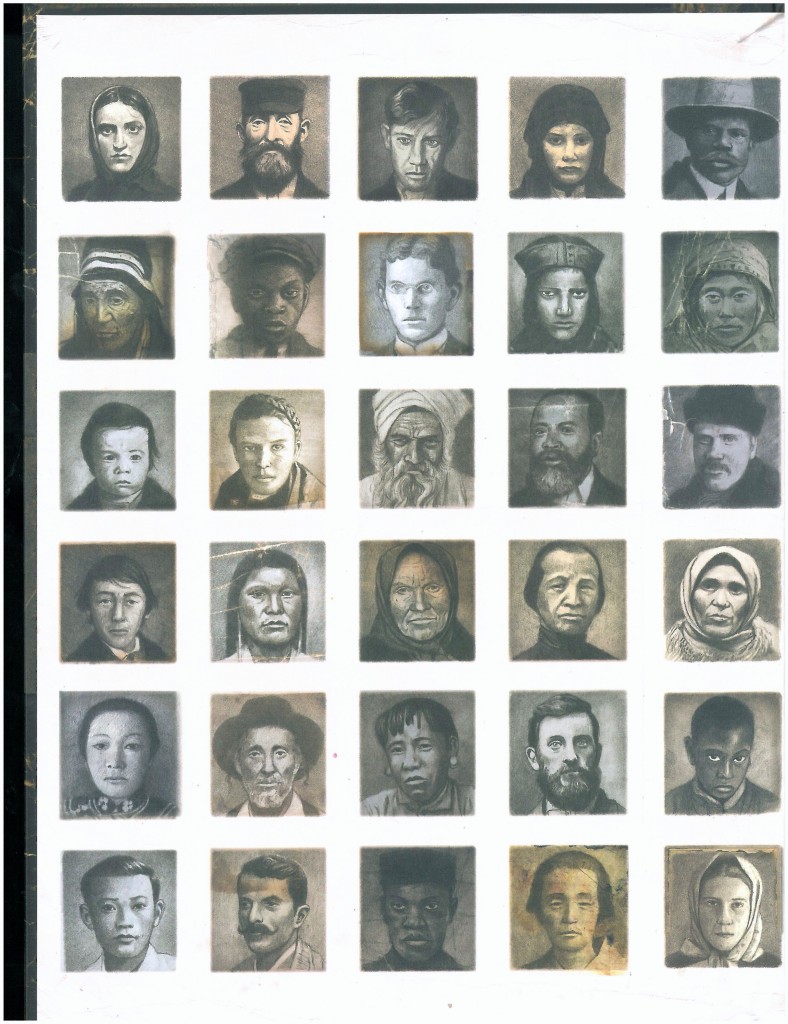

Almost immediately, I ran into several of those moments that Vicki Vinton talked about in a recent post where the students she read to jumped to conclusions that seemed problematic. After the cover page, Tan presented us with this magnificent two-page spread:

I asked the children what they made of these. They thought for a moment, and then several children began to form a conclusion.

Me: What do you think about these pages?

Student A: Hmmm. It looks like these are terrorists. (Others agree.)

Me: (Taken aback.) Terrorists? What makes you think that?

Student A: Well, I’ve seen people look like that on the TV when my mom watches her news.

Me: What is it about them that you recognize?

Student B: I agree with (Student A). They look like terrorists because some of them have those hats that they wear on their heads, the ones that twist up…

Me: (To myself: Oh no! This isn’t going where I expected…or want…or anywhere good.) Ok. We think these people might be terrorists. Why do you think the author wanted us to be thinking about terrorists right now in the book?

Student C: Maybe because something is going to happen that’s really bad and the author wanted to plant a clue for us right now?

Me: (To myself: Hmmm….that’s pretty good thinking about how authors use these early opportunities in books.) Ok. Maybe the author wants to warn us about something. Let’s read more to see if we can connect anything to these pictures and to other parts of the book.

(Before I can start to flip the pages again.)

Student D: Maybe they are slaves?

Me: (To myself: Hmm…this is going to be interesting!) Why do you think that?

Student D: They look like they aren’t very happy and some of them look like the pictures I’ve seen of slaves. Besides, there’s a picture of a little kid on the third row down on the left side and I don’t think this kid is a terrorist, but I know that some kids were slaves.

Me: Ok. So now we have two different ideas about what these pictures mean. 1) They are a warning that terrorists might attack. 2) They are pictures of slaves that…what?

Student D: …might be arriving somewhere. That way we can connect to the title, too.

* * * * * * *

We read on. The pictures tell the story of a man leaving his family. We notice they are poor, and the woman and man are very sad to be parting.

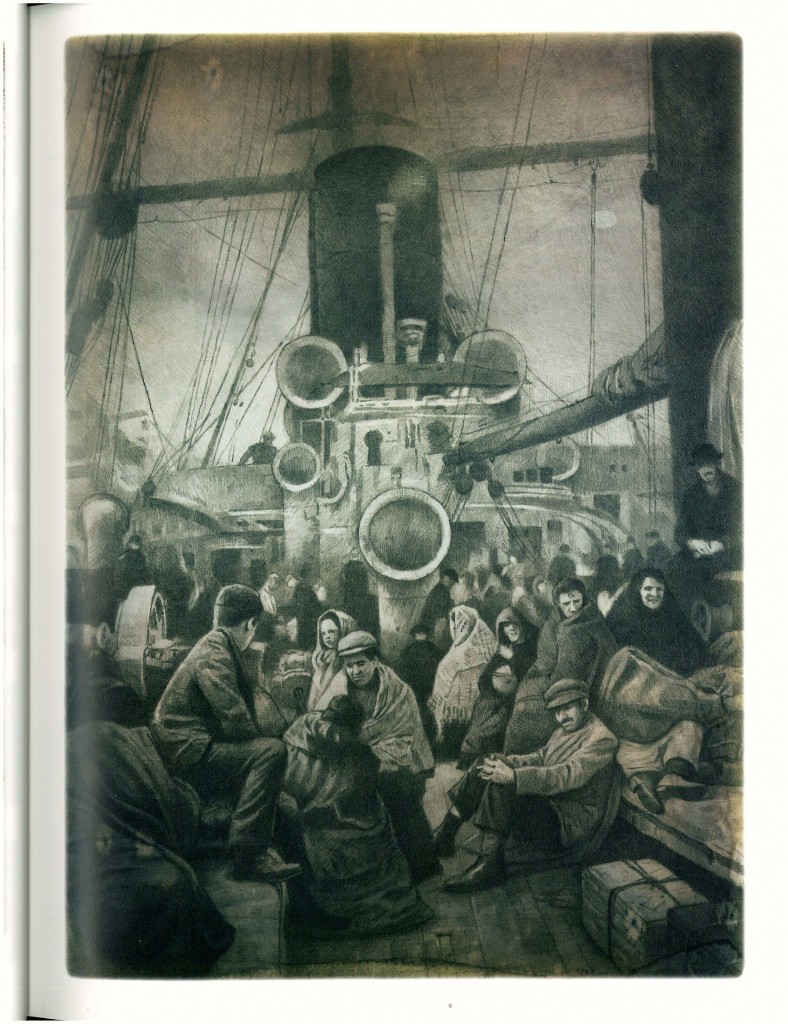

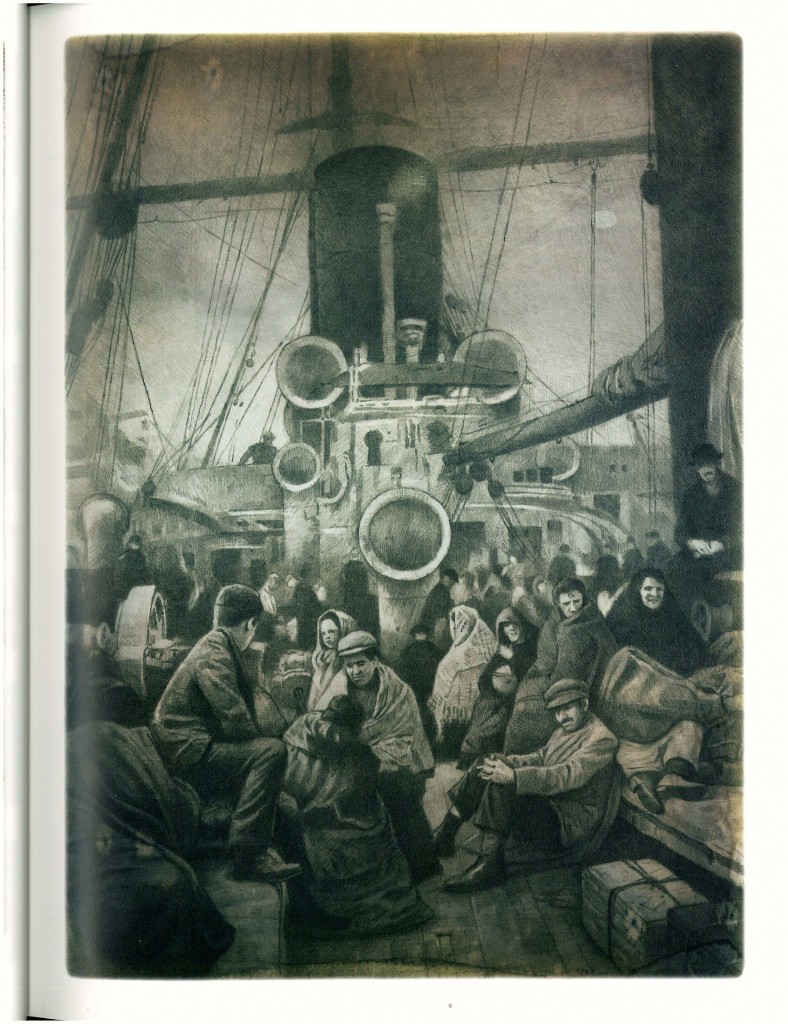

The man takes a train from the station and then boards a boat. After many days at sea — delightfully rendered by many small drawings of different kinds of clouds — we see this picture.

Suddenly, the ideas about who those people were at the beginning of the book changed!

Student A: I don’t think those were terrorists or slaves anymore. I think they are the people that got on this boat.

Me: Tell me more.

Student A: I think the author wanted us to think about all of these different people getting on a boat to go somewhere. They are sad because they have left their families, like the father was sad when he left his family.

Others: Yes! There are all of these people that had to leave their families and go on a train, maybe, and now a boat and soon they are going to arrive somewhere else.

Me: (To myself: I’m glad that I just let the early stuff go so we could come to this.) So, we discovered something here, didn’t we? We started out thinking th0se people were terrorists, then slaves, and now we think they might be other people, lots of different people who look very different from each other — all of whom are leaving their own homes for somewhere else. You’ve connected this set of images to other things you’ve noticed in the story and you’ve changed your mind as you got more information. That’s really cool, kids, that you can stick with something like that until it starts to make sense, and until you can connect it to lots of other details in the story. Congratulations.

Let’s see where this new idea takes us, okay?

* * * * * * *

It may be that the struggle the children engaged in as they jumped to conclusions helped them to first notice the differences between the immigrants in the two-page spread of faces (the strange faces, the long beards and mustaches, the wrapped heads.) This is a crucial understanding that I hoped they would get, that all immigrants are not alike, and that not all immigrants would even feel comfortable around the other, though they share the same “name”: immigrant.

Perhaps it was necessary for them to live with the idea of difference, even if it brought them to a place that was pretty uncomfortable for me for awhile. (Watch out for the terrorists!) Only after living with that for awhile were they able to understand that while the difference between the people on that page was significant for the story, the terrorist idea didn’t fit and they could eventually discard it.

Similarly, their conclusion jumping — they are slaves! — emerged from noticing the expression on the faces and putting that together with the differences in the faces. This idea of unhappiness or worry, too, might have been necessary for them to notice and to live with for awhile so they can feel deeply the emotions those who leave must feel.

As we read further in the story, the difference between the people, as well as the worry and sadness they had on their faces, might help us better understand what it must be like to be so different, one from the other, and so alone in a new world.