Photo Credit: Aaron Escobar via Compfight

One of the benefits of teaching many different subjects (as I do in fourth grade) is being able to come back to an idea or a question over and over again. Too often we think of learning happening in neat little packages: I taught this lesson and now I’m moving on to the next one. But learning doesn’t happen in nice, neat packages very often. It occurs in what I think of as seasons, with long periods of fallow and subterranean root development between harvests.

I was reminded of this kind of episodic learning once again this week. We’ve been exploring some questions related to immigration through a wonderful immersion project with a local museum. One of our reading groups recently finished an informational book on Ellis Island, took some notes on its content, and is now working up a video to teach the other kids in the class about what happened there. They’ve written the script and this week they are downloading photos from a marvelous collection offered through a photo stream from the New York Public Library via the Creative Commons.

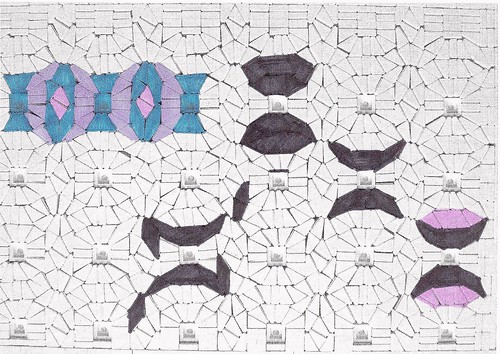

At any rate, the kids came across many, many photos that looked like these.

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

- New York Public Library via Flickr No known Copyright Restrictions

Then something interesting happened. The kids stopped and stared at the photos.

It turns out that the kids were looking closely and making connections to the drawings from The Arrival, a wordless graphic novel I had used to introduce our immigration unit. Said they, “These look a lot like the pictures we saw at the beginning of The Arrival!”

“Hmm…” I said. And I trotted over to get the book.

You see what you think.

So, then the connections came flying.

“Those people in The Arrival are definitely immigrants!”

“They look almost exactly the same as the drawings!”

“I wonder if the author saw these photos and drew the pictures from them.”

“Now we can see where the immigrants are from!” (The country of origin is in the notes on the Flickr account.)

So, maybe this connection between our reading of The Arrival and the New York Public Library’s photo stream isn’t the biggest thing that ever happened. But since our first interpretation of that page of faces from The Arrival was “Those look like terrorists!”, we have come a long way!

I think the struggle we went through to understand the drawings helped set the students up to not just KNOW that many different immigrants came through Ellis Island, this struggle also helped them OWN that difference in a deeper way than if I had told them from the outset, “No, those are not terrorists. They are immigrants.”