I’m a learner. Friends know I always seem to have an “obsession” with some new or continuing project. We joke about it. I pester them with questions about what they are thinking, and try not to bore them (too much!) with my own new learning. One long-term learning project has been to become a potter. This post will explore that passion in order to look for clues about how I’ve become a life-long learner. What can my own experience tell me about how I can be a better teacher, someone more able to help students discover the joys I’ve been able to discover?

Becoming a potter

I started making pottery when I was in my late-20s and a history graduate student at the University of Minnesota. I had gone far enough into the program to realize that I wouldn’t finish my degree. Then, I stumbled upon a community center with an old electric pottery kiln, some rudimentary classes, and I began to make pottery around the edges of my life.

I started making pottery when I was in my late-20s and a history graduate student at the University of Minnesota. I had gone far enough into the program to realize that I wouldn’t finish my degree. Then, I stumbled upon a community center with an old electric pottery kiln, some rudimentary classes, and I began to make pottery around the edges of my life.

After leaving graduate school, I took pottery even more seriously, eventually selling pots in a couple of art galleries and participating in a regional studio arts tour. While nowhere close to an actual living, this was a serious enough passion that the word hobby didn’t quite work for me. What caused that kind of commitment to learn something to that level?

The importance of making stuff

For me, there is something deep inside that likes making stuff. I learn well when I get a chance to try things and see them come to life. I suspect that making stuff is important to others’ learning as well. But what is it about making stuff that is so important?

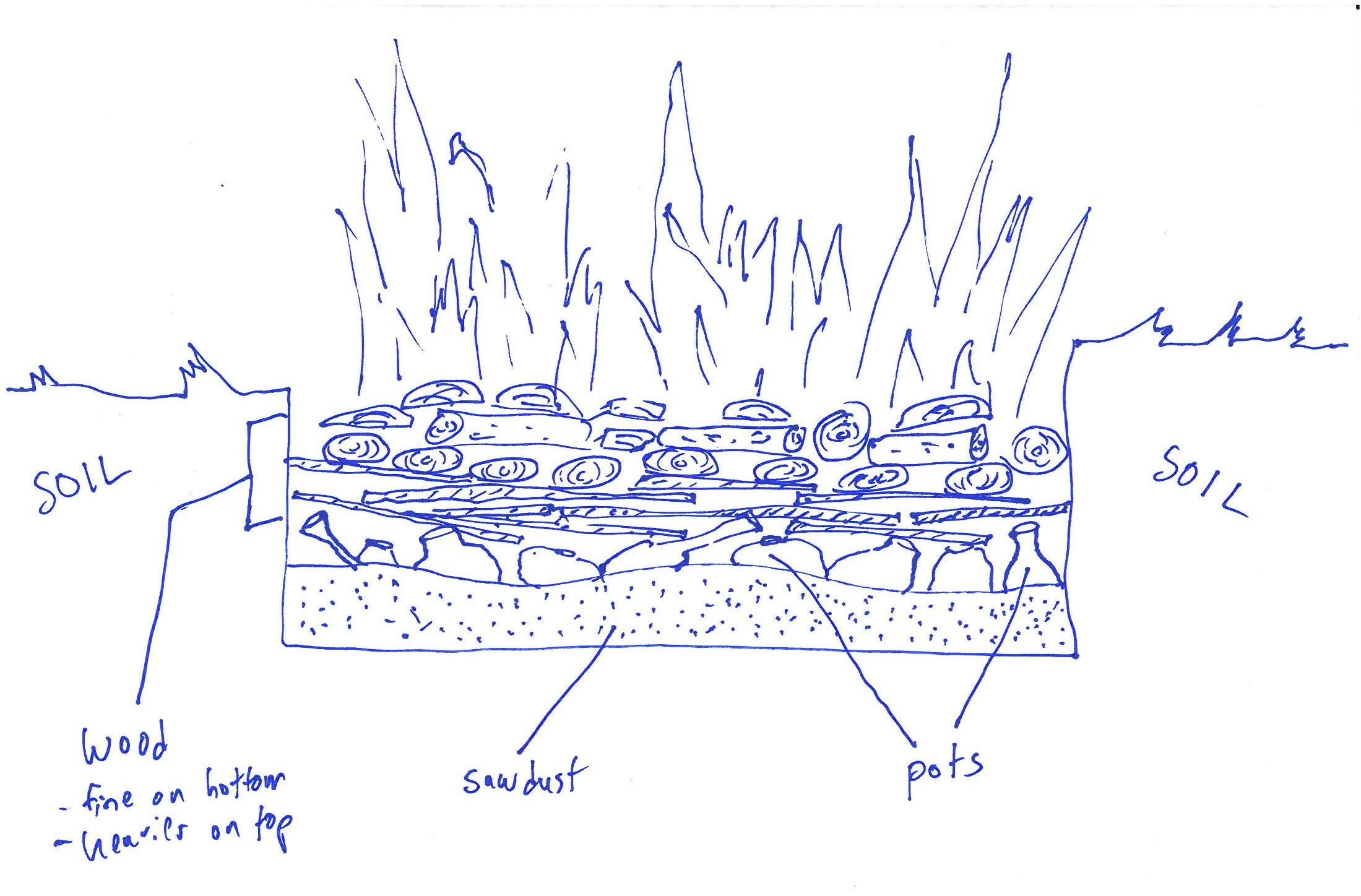

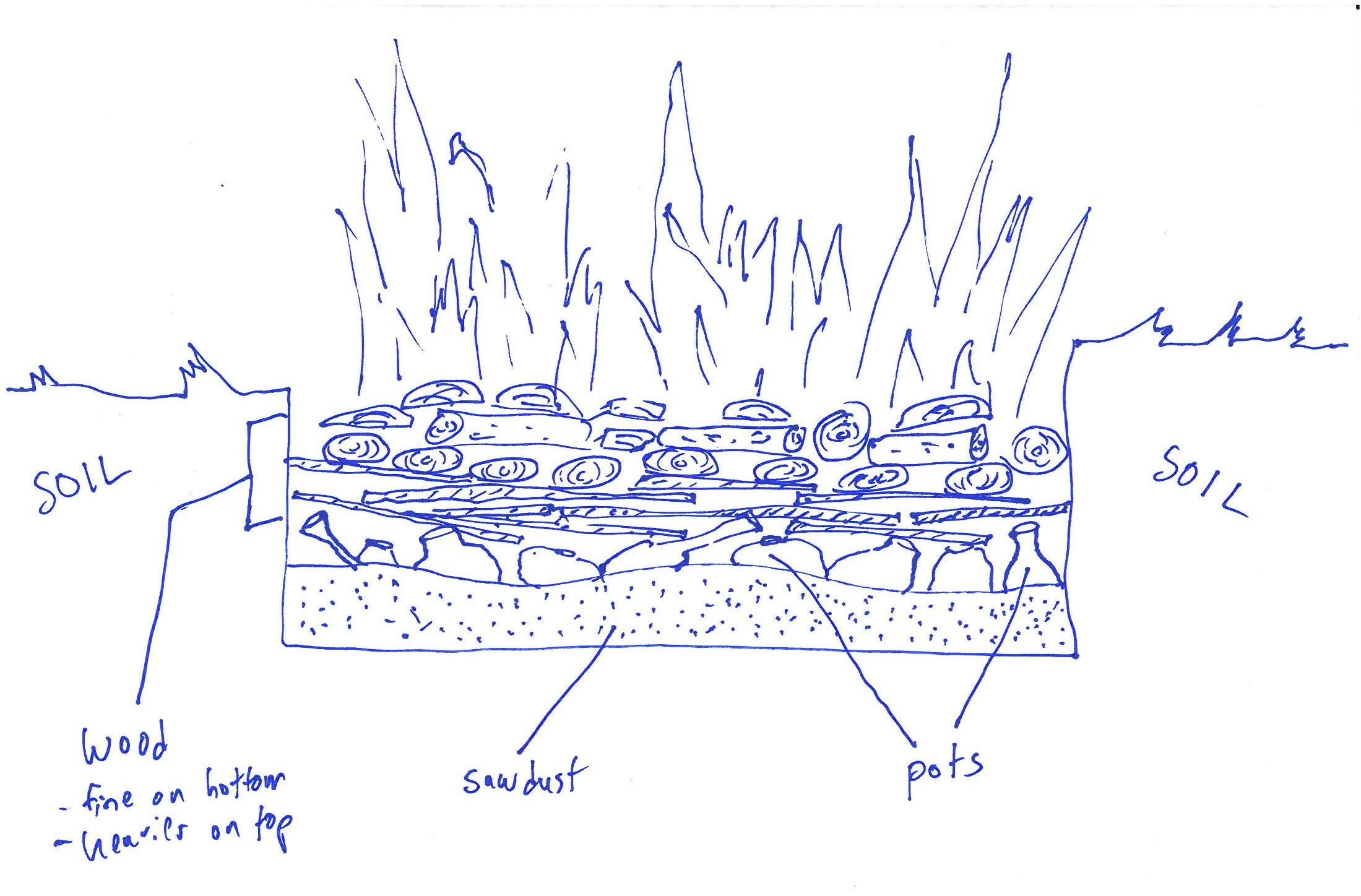

Wedging and preparing the clay, the motion of my hands while forming the pot, building the fire pit, all of these gave me a kind of pleasure that I wanted to feel over and over again. Perhaps this is the same internal process that musicians describe as being “in the music” watching it unfold just ahead of them as they play. Making stuff put me in the moment.

Being in the moment is hugely important to learning (and creativity.) Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi talks about the importance of “flow” in learning. I suspect that making stuff helps to create this sense of “flow” in the learner. Certainly it did with me. Sometimes hours would pass as I worked in my studio. I wasn’t aware of what was happening, except to feel the passage of time in the muscles in my back and legs.

I suspect the experience of making stuff was “flow” for me partly because it was not simply a “head” experience, but a body activity. Sure, I tried to make stuff that was in my imagination — in my head — but the experience of making stuff was primarily about maintaining a “feel” for the materials I worked with. Each clay was different, porcelain different than earthenware. Different air moisture and temperature also mattered. Warm, moist summer air caused the growing pots to react differently than cool, dry winter air. As I worked and discovered more about the material, I gained a sense of competence that was heavily dependent on what my hands “knew” about the moment of creation. I suspect that one of the big benefits of using one’s hands to make stuff has to do with developing a sense of “feel” for the materials that is quite different than the “know” of a purely mental activity.

So, the act of making stuff was important.

On being mentored

Mentors were important, too. A mentor is an experienced or trusted adviser. Mentors can help identify next steps for learning, help consolidate the learning that has already occurred, and provide support for the weary soul when learning gets difficult and the end is NOT in sight.

Most of the time when I think of mentors I imagine people. Interestingly, customers were some of my first mentors. I worked in an artisans’ gallery that sold my pots as well as the work of other artists. In the course of the work, I was able to talk to people who really liked my pottery. Their insights about what they liked help me understand how others saw it, and it helped me articulate to others what I was trying to achieve. All of that pushed me to learn more so I could grow and become more proficient. Potters and artists have been mentors to me, too. I think of fellow potters in Dubuque, IA who included me in a delightful potters’ community, taught me how to fire with wood, and asked that I teach them how to fire in a pit in the ground. Their inclusion validated my growing knowledge and, as a result, pushed me toward new knowledge. I felt like my work would be seen and known. Their friendship helped me gain an identity as an artist that was crucial for my own growth.

However, some of my most consistent “mentors” have not been people.

Early in my learning I came across magazines like Ceramics Monthly and Clay Times that were filled with photos of pots. These pointed me toward artists whose work I liked and respected. I used these connections to explore their work and their processes. While I actually met very few of them, I did create a portfolio of pots that inspired me. I’d later come back to these photos and stare at them for long periods of time, imagining what I would have to do to make pots such as these. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was creating a photo version of a “writing notebook” where I could store ideas and plan new work.

Another set of mentors were clay (and gravity!) The combination of these taught me a lot about clay as a material, what it could do and what it couldn’t. Interestingly, as I learned what it could do, my failure rate went down, but I would lose its voice in my work. I could feel the tension leave the pots; the forms become just a little bit safer, more predictable, and less alive. When things got too comfortable, I tried to push the material a bit farther. The conversation between me, the clay, gravity, and the forms would start again. It seems strange to think of a material as a mentor, but by listening to what clay was teaching me about itself, I was able to attempt new forms, which helped me to try new firing processes, which allowed me to make different kinds of pots. It was a journey.

Finally, I spent hours and hours sitting by the fire pit watching wood burn around the pots I made. The pit-firing process is harsh and unforgiving. I learned a lot from it. Many times I’d hear the explosion of pots as they heated beyond what they could withstand. But by spending all that time watching the flames burn around them, I discovered much about how fire seeks oxygen, and how air and flame move around clay forms. The fire taught me which forms tolerated extreme heat and which ones didn’t; it taught me how flame-designs were laid down onto (and into!) the surface of the clay by cool, smoky fires and hot, blue fires. After the fire died down, I would examine the pots to read the story of their travel through the flame.

Finally, I spent hours and hours sitting by the fire pit watching wood burn around the pots I made. The pit-firing process is harsh and unforgiving. I learned a lot from it. Many times I’d hear the explosion of pots as they heated beyond what they could withstand. But by spending all that time watching the flames burn around them, I discovered much about how fire seeks oxygen, and how air and flame move around clay forms. The fire taught me which forms tolerated extreme heat and which ones didn’t; it taught me how flame-designs were laid down onto (and into!) the surface of the clay by cool, smoky fires and hot, blue fires. After the fire died down, I would examine the pots to read the story of their travel through the flame.

Making pottery helped me develop and hone a cycle of learning that has been important in other areas of my life. For me, learning something often starts with a large amount of time (and a push to change.) Early in the pottery making journey those came through a transition out of graduate school and into a period of under employment. But beginning was more than a kick in the pants, and idle hands. I also felt a drive to make stuff, to build something tangible that could be experienced by myself and others. Once that long period of experimentation (dabbling?) occurred, I found some important response to my work from others who understood what I was trying to do (artists and customers.) Finally, from early on in the process and extending all the way through the my learning, I found something intrinsically motivating about both the making and the materials. There was something about the hand and heart work that pulled me through periods without much interaction with people.

As a teacher, maybe I can help students experience this process for themselves? If I could, that would make me very, very happy.

Do you have a similar experience with learning? What am I missing about learning?

I started making pottery when I was in my late-20s and a history graduate student at the University of Minnesota. I had gone far enough into the program to realize that I wouldn’t finish my degree. Then, I stumbled upon a community center with an old electric pottery kiln, some rudimentary classes, and I began to make pottery around the edges of my life.

I started making pottery when I was in my late-20s and a history graduate student at the University of Minnesota. I had gone far enough into the program to realize that I wouldn’t finish my degree. Then, I stumbled upon a community center with an old electric pottery kiln, some rudimentary classes, and I began to make pottery around the edges of my life. Finally, I spent hours and hours sitting by the fire pit watching wood burn around the pots I made. The pit-firing process is harsh and unforgiving. I learned a lot from it. Many times I’d hear the explosion of pots as they heated beyond what they could withstand. But by spending all that time watching the flames burn around them, I discovered much about how fire seeks oxygen, and how air and flame move around clay forms. The fire taught me which forms tolerated extreme heat and which ones didn’t; it taught me how flame-designs were laid down onto (and into!) the surface of the clay by cool, smoky fires and hot, blue fires. After the fire died down, I would examine the pots to read the story of their travel through the flame.

Finally, I spent hours and hours sitting by the fire pit watching wood burn around the pots I made. The pit-firing process is harsh and unforgiving. I learned a lot from it. Many times I’d hear the explosion of pots as they heated beyond what they could withstand. But by spending all that time watching the flames burn around them, I discovered much about how fire seeks oxygen, and how air and flame move around clay forms. The fire taught me which forms tolerated extreme heat and which ones didn’t; it taught me how flame-designs were laid down onto (and into!) the surface of the clay by cool, smoky fires and hot, blue fires. After the fire died down, I would examine the pots to read the story of their travel through the flame. This post starts as a short story (with no real ending) and then moves into an exploration of my own experience with learning in elementary school. Future posts will explore other places and times where learning has happened in my life. I’m hoping that by exploring my experience with learning, I will discover what I can do to help others learn, too. Or at least notice more of the learning (and learning possibilities) that surround me.

This post starts as a short story (with no real ending) and then moves into an exploration of my own experience with learning in elementary school. Future posts will explore other places and times where learning has happened in my life. I’m hoping that by exploring my experience with learning, I will discover what I can do to help others learn, too. Or at least notice more of the learning (and learning possibilities) that surround me.