Lately, I’ve been trying to understand the Common Core (CC) standards; what they are, what they mean, and their implications for teaching and learning. To help with that task, I’ve been reading a good book by Calkins, Ehrenworth, and Lehman, Pathways to the Common Core, and devouring a great blog by Jan Burkins and Kim Yaris. I’ve also been taking a workshop through my area education association (a regional source for professional development), and I’ve been talking to my colleagues.

Lately, I’ve been trying to understand the Common Core (CC) standards; what they are, what they mean, and their implications for teaching and learning. To help with that task, I’ve been reading a good book by Calkins, Ehrenworth, and Lehman, Pathways to the Common Core, and devouring a great blog by Jan Burkins and Kim Yaris. I’ve also been taking a workshop through my area education association (a regional source for professional development), and I’ve been talking to my colleagues.

One thing all have said is that the CC is moving away from reader response theory toward the text as the all-important element in the reading experience (back to ye old, New Criticism.) Certainly one of the developers of the CC, David Coleman, has (eloquently?) pointed this out through statements like this: “…as you grow up in this world, you realize that people don’t really give a sh*t about what you feel or what you think.” To justify this stance, Coleman goes on to say, “It is rare in a working environment that someone says, ‘Johnson, I need a market analysis by Friday but before that I need a compelling account of your childhood.” (I first came across Coleman’s quote in a post about the last NCTE annual convention at Vicki Vinton’s top-notch blog.)

One way Coleman is right

First of all, there just aren’t teachers who think a “compelling account of your childhood” is sufficient to succeed. That’s a straw man, David. It makes your point by trying to make teachers look stupid. I don’t like that.

However, what if we teachers don’t ask our students to think deeply enough, clearly enough. No teacher likes the “I have a puppy, too” response to literature, but maybe we’re not asking enough of our students. Maybe we ask students to write personal narratives too many times, and don’t ask students (or ourselves!) to question what we discover from that reflection. Maybe, like Coleman, we indulge ourselves in a straw man or two to joust, rather than push to figure out the real issues we need to deal with.

If so, then we need to do a better job of teaching better thinking. We need to help students see the larger world around them, to interact with that world, and to wonder and to learn from it, too. That’s a big and noble project. And, if this is what David Coleman means in his vulgar way, then I’m hep with that jive.

One BIG WAY Coleman is wrong

While employers won’t ask for compelling accounts of childhood, it’s just not true that no one “gives a sh*t” about what we think and feel. Authors care. They construct their stories around our feelings. Advertisers care. They don’t sell their products through convincing argument that we carefully consider before we act. They play directly on our feelings. Politicians care. While we think we make decisions based on careful analysis of policy decisions, there are many studies that show we actually decide based on how well those decisions fit the narratives we have about the world.

In fact, as I’ve been reading Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, I can see just how much our intuitive, feeling, emotional self is wrapped up in all of the decisions we make, in all of the data we analyze, in all of the actions we take. Our minds often fit evidence to intuitive belief; we don’t often change belief based on evidence.

In fact, as I’ve been reading Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, I can see just how much our intuitive, feeling, emotional self is wrapped up in all of the decisions we make, in all of the data we analyze, in all of the actions we take. Our minds often fit evidence to intuitive belief; we don’t often change belief based on evidence.

Wouldn’t it be a good idea to know that self a little bit better? To see how it thinks? To understand what it believes? On the most basic level, what would the last 3-4 years have looked like if some mortgage lenders, or investment bankers, or re-insurance executives had said, “Johnson, I need those profit margin projections by Friday, but don’t forget to reflect on how your decisions reveal what is most important about you, as a person, and what they will say about me, as a boss.” A little CRITICAL engagement with ALL of one’s feelings–not just avarice–might not have been so bad.

An example from the classroom

So, what does this all have to do with classroom teaching?

I was thinking about all this stuff the other day and decided to return to a set of questions that came up while we were reading Bruce Coville’s, Goblins in the Castle. There’s a section, early in the book that introduces a character (Nurse) and then drops her in the castle moat within the space of a sentence. We never hear from her again.

The kids didn’t know what to do with this information at first. They worried about the main character, William, who was without the Nurse as he grew up. They worried about the Nurse because they hadn’t experienced a lot of stories where characters are introduced, then “gotten rid of” in this way. What to do with this? For quite awhile in the story, the students really wanted her to come back into the story, even inventing a possible re-entry for her as the wife of Igor, William’s new friend from the dungeon below the castle. It was clear to me that the students thought this would be a satisfying way to connect some loose ends together.

The kids didn’t know what to do with this information at first. They worried about the main character, William, who was without the Nurse as he grew up. They worried about the Nurse because they hadn’t experienced a lot of stories where characters are introduced, then “gotten rid of” in this way. What to do with this? For quite awhile in the story, the students really wanted her to come back into the story, even inventing a possible re-entry for her as the wife of Igor, William’s new friend from the dungeon below the castle. It was clear to me that the students thought this would be a satisfying way to connect some loose ends together.

That never happened.

So, after the story was over, I thought about what we might learn from our earlier wonder about Nurse. What if we just made it EXPLICIT that authors want readers to feel things, and then we could take those feelings as evidence of something important in the story. Instead of dismissing our feelings, what if we really try to examine them, find out what they are, how they were created by the author and us, and what that means about what the author wanted to say? In doing so, WE become part of the story.

I started out like this:

We know that authors talk to us through details. We know those details make us think about things…but they also make us feel certain ways. We know that the author was making those choices about details for a reason. Do you remember that time early in the story when Nurse fell in the moat and was never heard from again? Here: I’ll re-read it for you. This time, I want you to pay close attention to what you are feeling as you hear about this event. See if you can figure out how the author was trying to make you feel that way.

It was a fascinating discussion.

The students almost universally felt “sad.” We pushed that feeling because “sad” is one of two or three default descriptions of feelings in third grade. As we pushed, words like “worried about William’s future” emerged (“He’s just a little baby! I was worried that he’s lost the one person who was taking care of him like a parent might take care of him…) Also “lonely”: (“That part made me feel so lonely. Now William doesn’t have anyone who really loves him. Later we found out that the Baron doesn’t even remember his name after eleven years! That part made me feel so lonely. It reminded me of how much my parents mean to me.”)

We then went the next step, which was to ask: Why would the author have wanted you to feel lonely and worried for William?

Their answers searched to connect pieces of the story together, to explain how by making us feel William’s loneliness so strongly early on in the story, to surface our concern (worry) for William, we felt so happy that he found Igor later and was successful in his task. And when Coville added the character Herky, who we decided seemed like a cross between a family pet and a little brother, and the character, Fauna, who seemed like an older sister, we could FEEL the strength of William’s growing “family.”

I think this discussion points me toward making feelings a BIG AND IMPORTANT PIECE of evidence because people really should (and do) “give a sh*t” about them. Rather than be satisfied with the “I have a puppy, too” response, I’m going to try to drill down into those feelings more deeply. What, exactly, are you feeling? What did the author do to make you feel that way? Why did the author want you to feel that way?

I’m just now finishing Peter Johnston’s wonderful book, Opening Minds. I loved his earlier book, Choice Words, and this one is a great read, too.

I’m just now finishing Peter Johnston’s wonderful book, Opening Minds. I loved his earlier book, Choice Words, and this one is a great read, too. I know which pathway I want to follow! For now, I’ll have to trust that when the tests come ’round the mountain riding six white horses when they come, the kids will be ready because they’ve cared enough about ideas to know why they cite evidence in the first place…

I know which pathway I want to follow! For now, I’ll have to trust that when the tests come ’round the mountain riding six white horses when they come, the kids will be ready because they’ve cared enough about ideas to know why they cite evidence in the first place…

While this framing seems like a subtle difference, since understanding is the result of both methods (hopefully!), the difference has immense implications for how readers engage with texts.

While this framing seems like a subtle difference, since understanding is the result of both methods (hopefully!), the difference has immense implications for how readers engage with texts.

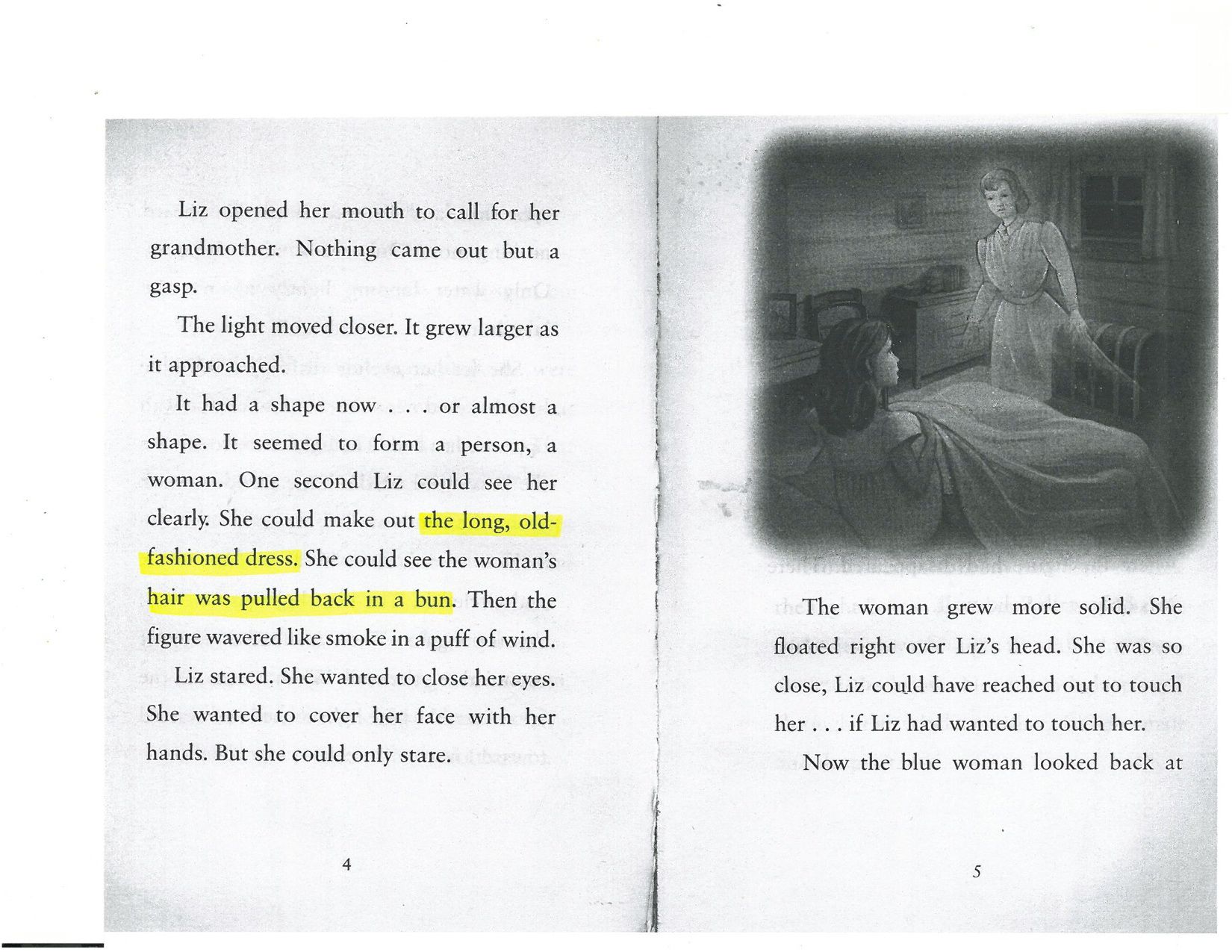

We started out by looking at the cover of the book, which shows a ghostly blue figure floating above a wooden floor, and the title, The Blue Ghost. Obviously, this illustration and title got the kids wondering about this figure: Who was it? Was it a real ghost? Where was it? How did she die?

We started out by looking at the cover of the book, which shows a ghostly blue figure floating above a wooden floor, and the title, The Blue Ghost. Obviously, this illustration and title got the kids wondering about this figure: Who was it? Was it a real ghost? Where was it? How did she die?

For deeper learning to occur, teachers “should use modeling and feedback techniques that highlight the processes of thinking rather than focusing exclusively on the products of thinking.” So, we teachers should strive for not just knowledge transmission, but developing the student as a thinker. Furthermore, this process isn’t easy. The authors go on:

For deeper learning to occur, teachers “should use modeling and feedback techniques that highlight the processes of thinking rather than focusing exclusively on the products of thinking.” So, we teachers should strive for not just knowledge transmission, but developing the student as a thinker. Furthermore, this process isn’t easy. The authors go on: What needs to be done

What needs to be done