What should the children know and be able to do?

My teaching work is to design lessons around the answers to this question. And I do. But then, like the other day, something happens that reveals the vast chunk of learning that never made it into the standards. Yet, this is the learning that sometimes seems most important to me and causes me to remember that “career and college ready” does not encompass some of the most important learning in our classroom.

The week before Thanksgiving we spent some time writing descriptions. My goal was to help the children be able to organize their own thinking and their writing. They will use these skills as they write informational pieces later this month. From our work, they will be able to describe an object with precision and artfulness.

This seems a worthwhile set of skills to learn. I love elegant, clear thinking. Certainly this kind of precise thinking and writing would be a boon in most careers; colleges might really groove on those, too, though sometimes I wonder if artfulness might be less well appreciated in many careers and colleges.

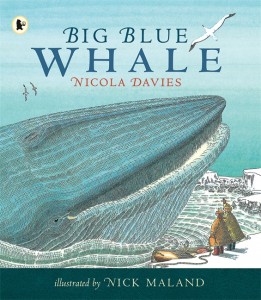

We began by studying several of Seymour Simon’s descriptions. You can pick just about any of his books since they are filled with great description. We ended our study with Nicola Davies’ short description of the outside of a blue whale from her book, Big Blue Whale.

We began by studying several of Seymour Simon’s descriptions. You can pick just about any of his books since they are filled with great description. We ended our study with Nicola Davies’ short description of the outside of a blue whale from her book, Big Blue Whale.

The blue whale is big. Bigger than a giraffe. Bigger than an elephant. Bigger than a dinosaur. The blue whale is the biggest creature that has ever lived on Earth!

Reach out and touch the blue whale’s skin. It’s springy and smooth like a hard-boiled egg, and it’s slippery as wet soap. Look into its eye. It’s as big as a teacup and as dark as the deep sea. Just behind the eye is a hole as small as the end of a pencil. The hole is one of the blue whale’s ears — sticking-out ears would get in the way when the whale is swimming.

We noticed the way Simon and Davies started big — to give an overview of the object to be described, to help the reader see the big picture — before diving into the details. We noticed how good description is organized to help the reader assimilate this new information in an organized and logical fashion. We noticed how good description often uses comparisons to help a reader attach the unfamiliar to the familiar.

The more the children looked, the more they saw the art contained in a good description.

Over the next several days, we described various items around the classroom, practicing our craft. Then, just to see what they would do, I brought in some cut stems of Indian grass, a large prairie grass that grows in the prairie we are trying to grow on the hill near my house. I thought the children might be interested in this very large version of a common plant: grass.

Indian grass from the prairie on the hill above my house.

They were.

The children each took a piece to study. They measured against the tiles on the floor; each stem was between 5 and 8 feet tall! They marveled at the size. They marveled at how different turf grass is from prairie grass. And how similar, too.

The children each took a piece to study. They measured against the tiles on the floor; each stem was between 5 and 8 feet tall! They marveled at the size. They marveled at how different turf grass is from prairie grass. And how similar, too.

They looked carefully at how the grass was put together. They began to name the parts, because in order to describe well, you have to name the parts. This need to notice and name parts helped the children see why science is so dense with vocabulary. Scientists must look closely at things, name the parts they see, and then describe them clearly.

At first, the children only saw the stem and the seed head. Some saw the leaves, but these thin strips don’t look like what they are used to calling leaves. The more they looked, though, the more parts they saw. They did not know the technical terms for all of the parts, but to describe well, they needed to call them something. So they set out as explorers, naming the new lands they saw. For instance, what are you going to call the little “hairs” that protrude from the flattened end of the seed? I urged them to think of the function these “hairs” might serve, and then give them a name that reflects that purpose. (Seed stickers. Seed grabbers. Seed attachers. These were some of the part-names they came up with.)

As they sketched, as they wrote, they began to see the wonder contained in the supposedly simple things around them.

Some saw how the large structures they noticed first (the long stem, for instance) are actually made from ever smaller structures, and these were made from even smaller structures, and so on. The more you looked, the more you saw. Where do you stop with your noticing? With your naming?

The stem is hollow! What do I call that hollow? Is it used for anything, or is it just hollow?

Did you notice the stem has sections? There are joints that separate those sections! It’s like the stem grows up to a certain point and then decides to stop and then it starts growing all over again!

The stem wall has all of these little strands of fiber in them. I wonder what they do? What are they for?

Some saw the connections between this grass and other plants they knew. (Some are farmers, after all.)

Indian grass looks a lot like corn, except the seeds are not all put together in a cob like corn, but in a spray of seeds. The leaves and the stem look like corn though.

Others began to see the overall symmetry of the basic grass design.

Did you know that Indian grass has the same pattern that repeats itself all the way up the stem? Each segment fits into the segment below it.

If you look at the seed head, even those tiny stalks that hold the seeds look just like the stem. They have all these little joints, but they are not nearly as big around as the stem farther down.

I wonder how the Indian grass knows how to stop growing up and when to start making a seed head?

Some saw patterns in the way the leaves came off the stem. Some, even wondered whether you could even call these leaves, since it looked like they were at one time part of the stem. Is a leaf a leaf? A stem a stem? When does one become the other?

I noticed that the leaves start at these joints and wrap themselves around the stem. Maybe they aren’t even different than the stem? But then they grow for awhile and separate from the stem. Why? How can a stem become a leaf?

When the children got to this stage in our investigation, it seemed to me that something special was happening. I told them that they were noticing things that only people who study plants, who look very closely at them, notice. And they were asking questions that no one knows the answer to, but scientists are very interesting in knowing these answers. “What, exactly, causes a plant to stop growing up and start to grow a seed head? What causes anything to change? What causes you to change? To grow?” These are important questions, important observations. I congratulated them.

For a moment, I stood there amidst the clamor watching the children run from plant to plant as they showed each other the discoveries they made. We’ll get back to the description, I thought to myself. But right then what seemed most important was to honor the curiosity bubbling through the room. And I’d be lying if I didn’t wonder how this kind of endeavor gets turned into an “I can…” statement, then packaged as a “skill” to be mastered.

So this time of learning, of exploration came, and then it went. And it DID take time; these moments don’t come free. If the moments we spent looking at grass, I mean really looking at grass, were “billable” hours in the great race to the top, under what standard would the Grand Accountant code them?

And yet, I know these times are important precisely because they reach so deeply inside.

Brilliant.

It seems like there should be a different billing system for the hours that honor wonder and creativity. The times when our teaching moves might not seem immediately productive, but might just be what plants the seed for our children to grow up with their eyes and hearts open to the world around them.

You know, Mary Lee, I DO wonder whether our lives might (literally) depend on whether we notice things as “small” as the place on the stem of grass where the leaves emerge…or the thickness of an ice sheet on an ocean a long ways from home.

I think it was Aldo Leopold who once said that the conservation ethic comes from a feeling of love. And a person can’t love if he doesn’t first notice.

Best to you!