I’ve been enjoying education writer Annie Murphy Paul’s Brilliant Report, a weekly dose of learning theory and research that arrives in my inbox. In the last few months she has written two posts (here and here) on travel. One post made the case that travel can help generate a sense of humility, an outlook that recognizes that there are many, many ways of doing things in this big ol’ world:

Exposure to other cultures (whether through travel or through encounters in everyday life) is one way we can keep ourselves cognitively humble; such experiences invariably remind us that our own perspective on the world is limited, and only one among many.

Travel helps us “to consider alternative scenarios or outcomes. Often we are so sure that things will work out the way we expect that we fail to account for other possibilities.”

I’m just now back from a two week trip to Chile with my partner, Beth, (an ecologist) and a friend, Anita, who is a Chilean anthropologist. We spent some time scoping out a location for a college class the two of them are going to teach about mining, tourism, people, and the environment in the Atacama desert of northern Chile.

For me, though, this trip to Chile (a place I had never been before) was a perfect opportunity to adopt a stance of openness, to see not just what lies on the surface, but to try, as best I could, to seek out what lies buried underneath. Or, as Annie Murphy Paul noted: “When in Rome…Learn Why the Romans Do What They Do.”

Valparaiso — One Kind of Beauty

One side trip took us to Valparaiso, a seaport city near Santiago that is filled with public art. My eyes feasted on the color. You don’t find this kind of exuberance very often in the staid Midwest, leaving me to wonder what kind of artistic ethos must pervade Valparaiso to account for this?

Buildings and doorways were painted with some of my favorite colors, and in combinations that were very exciting to my eyes!

And around each corner, vibrant public art was spray painted on the sides of houses, businesses, even on the many retaining walls that seem to prop up the hills.

But the majority of the time was spent in northern Chile getting to know the desert and its people.

Beneath the Surface of the Atacama Desert — Another Kind of Beauty

The Atacama is a fragile environment. Some parts have not seen rain in several hundred years. As tenacious as life is, even soil bacteria cannot grow in some places for lack of water.

Atacama Desert. Photo: Steve Peterson

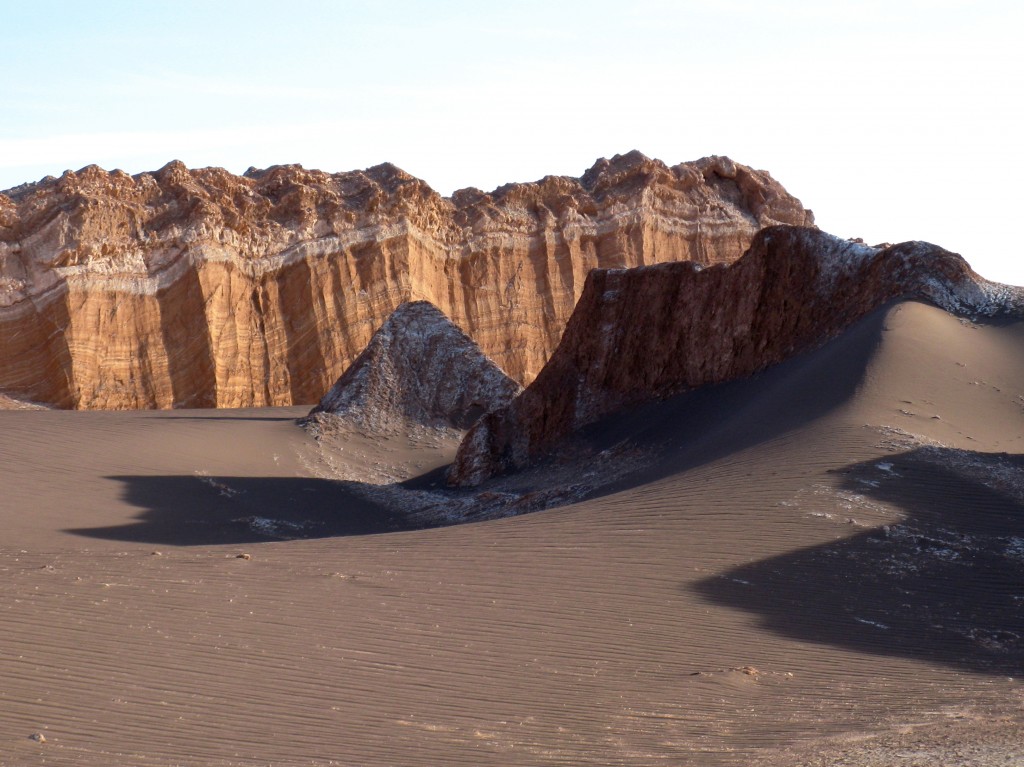

Over the centuries, sand has blown off the level spots of the desert leaving a hard pan of rock and pebbles. The sand, like snow, is carried by the winds to form drifts around any surface irregularity it encounters such as these uplifted sedimentary hills in the Valle de la Luna.

Valle de la Luna at sunset. Photo: Steve Peterson

Valle de la Luna, the white is salt from groundwater evaporation. Photo: Steve Peterson

More rain falls in the highlands, which brings grasses, and the vicuña that graze on the grasses. The grasses shone brilliant yellow against the crystal-blue sky. Behind, volcanoes loom.

Grasses near a laguna in the altiplano. Photo: Steve Peterson

The desert is filled with salt flats several thousand meters thick that are formed by ancient water from prior glacial events that slowly oozes up through mineral bearing rock back to the surface. With no outlet, the flats dry like an immense evaporation dish, creating a crucial habitat for three species of flamingos that eat shrimp from the briny waters and for many other birds, too. Some of the sandpipers that I see in Iowa winter in the Salar de Atacama. (We are more closely connected than I realized, this place and me.)

Flamingos in the Salar de Atacama. Photo: Steve Peterson

Life is tenuous in the desert. Flamingos compete for water with the lithium mines. It turns out that the Salar de Atacama contains more than 25% of the world’s lithium supply. Large quantities of lithium rich ground water is pumped to the surface and evaporated in large pools that you can see in the center of this Google Earth screen capture. (For some reason, Google Earth thinks this is the Salar del Carmen.) The batteries for my computer probably contain lithium mined in the Atacama. The flamingos live in small salt ponds north of the mines. The water the mines take from the ground isn’t being replenished.

Lithium mine evaporation ponds as seen from Google Earth.

And desert life is hard for people, too. Growers in the small town of Tocanao grew fruit on the fertile floodplain in a small slot canyon along a sweet water river that came from the mountains. Until, that is, a freak rain in the mountains four years ago created floods that swept away not just the fruit trees, but also all of the topsoil, leaving bare rock behind. Desert life is life on the edge. And living on the edge gets even more difficult with extreme weather caused by climate change.

A few years ago fruit trees grew along the river. Photo: Steve Peterson

People become ingenious in order to survive. They settle in small towns along small streams and use terracing techniques to capture and hold water. It is amazing to think of the accumulated knowledge these growers have about seeds, watering cycles, and farming in nutrient poor soils, not to mention the political skill it takes to manage systems like this in such an extreme environment and under such scarcity.

Terracing in Toconce. Each family group gets a certain section of the terrace to work. Irrigation flooding happens on a set schedule and is worked out cooperatively. Photo: Steve Peterson

A house with window frames made of tires. The glass appeared to be a washing machine door. Bars are sticks embedded in adobe. Beautiful and practical! Photo: Steve Peterson

But this way of life is also changing. Minerals, especially copper, have been mined in the geologically active mountains throughout the Atacama region for many years. The Chuquicamata mine is one of the biggest open pit mines in the world. All it takes is a quick look out the airplane window to see how dominated the landscape is by mining and the insatiable need our world has for more and more.

The Chuquicamata copper mine as seen on Google Earth. 5Km long, 3Km wide, and 1Km deep.

All that mining uses a lot of water, which is in short supply in the desert. The mining caused the water in some towns to dry up, which caused the food supply to be tight, which caused some of the Atacameños who lived in those towns to move to the city of Calama, a dingy mining town on the Loa River.

And it was in Calama, that I saw some more inspiring sites and, through Anita, met some very interesting people indeed.

Making Likantatay — Still Another Kind of Beauty

Unfortunately, I don’t have many photos of Likantatay. I’ll have to describe it with words.

Likantatay is Lila’s home turf. Lila is an Atacameña from one of the villages who now lives in Calama and works at a local school. Anita met Lila when she did some of her anthropological research in the desert communities.

We drove to the outskirts of Calama to meet Lila early one morning. She had agreed to show us her home community of Caspana, a two hour drive northeast from Calama, and to introduce us to some of the people there. The sun was just coming up as we left the paved roads of Calama and entered a section of town that contained rutted, dirt streets. Fences made of wooden pallets and rusted corrugated metal siding lined both sides of the road. Gaps in the fences revealed patches of desert with what appeared to my eyes to be random piles of debris — rock, concrete from road destruction, wire, and metal. It looked like a dumping ground for city residents. I thought we were lost.

Our meeting place turned out to be an intersection of two dirt streets. We parked near a low cinder block structure. An old man rode slowly past on a squeaky bicycle in the chill desert air.

After some time, Lila appeared and lead us through a metal door and into the courtyard of her family’s compound.

Finally, I began to see beneath the surface. As we talked (with Anita translating) I began to realize that what had at first appeared to be a garbage dump was actually a long-standing community that represented the hope and dreams of many people.

The settlement of Likantatay was started by Lila’s mother and other Atacameños as a squatter community just outside the Calama city limits. After they moved from the villages (Toconce, Rio Grande, Caspana, Chui Chui, among others) the transplanted villagers felt a desire to keep some of the former ways of life in their new life in the city. They settled in communal groups, built homes from scavenged materials (the piles that I first saw as junk were actually raw materials for construction), and they developed fields to grow produce and grains (the patches of desert that I saw through the fences were actually fields that had no crops because it was winter in the Southern hemisphere.)

For several years, the Likantatay residents “stole” water from the sewage pipe that left Calama. They would open up the pipe at night when no one could see in order to water their fields. They raised corn and carrots and squash and potatoes, as well as livestock. (Lila’s family had several goats, sheep, pigs, llamas, and chickens in pens behind their compound.) They relied on their centuries old skills to share the water equitably among farmers.

Later, after much strife (including some sit-ins at government offices) the residents of Likantatay gained some legitimacy. And along with that legitimacy came services like electricity, sewer, and water (a canal was dug mostly by hand by Atacemeños, but through land that the city needed to free up.) Likantatay had become a part of the city.

It was also an important place for the Atacemeño diaspora to gather to support each other. The day we visited Lila’s home was already busy with food preparation. A large party was scheduled for later that day. One of the Atacameñas, now living in Santiago, had developed cancer. In response, the community had her travel back to Likantatay for a Mass for healing to take place around a homemade altar. They put on a feast to raise money for treatments. It matters to have a place to carry on these traditions. It matters that people wrested a home from the government and from the desert. Sometimes people need to come home.

So, my experience in Likantatay really did help me gain another level of humility, to realize that there were stories behind the fences and the piles of concrete and metal, that beauty takes many forms. The experience in the desert helped me see that stories of survival, tragedy, and triumph are layered around us like drifts of sand sifted and dropped by the winds that blow through our lives.

* * * * *

After a long day in the villages in the foothills of the Andes, we returned to Likantatay. The large communal kitchen in the compound was filled with women and girls cleaning up after the party. Jaime, a girl of about ten, asked if Beth, Anita, and I would go to the back and watch her show off some soccer moves she had been practicing. One thing lead to another and she challenged Beth and me to a soccer match, which got videotaped as it became increasingly hilarious. Somewhere making the rounds of Likantatay is a short video of Jaime kicking my butt, passing the ball to herself between my slow feet, juking, feinting, and making this old gringo jerk around like a marionette on a string. And that’s just one more small story to drift on top of the others.

What riches you have shared with us! The beauty is easy to love. The changes brought on by the need for moremoremore and by climate change are disheartening. Your storytelling is an important spotlight shining on the tenacity of the people of Likantatay. Thank you for taking us along!

Hi, Mary Lee!

It was quite a trip. Over and over again I was struck by how what I experienced was only one small part of a many-layered set of stories, none of which are easy to tell because they don’t have an end. Everything is provisional, even the relative triumph of the Likantatay community is subject to change at any moment. (And even their new legitimacy is a sword with two edges. For instance, the water from the river that they “won” is naturally laced with heavy metals, including high concentrations of arsenic, which has likely contributed to a cancer cluster.)

This experience has helped to remind me that there are layers of stories close to home, too. Maybe that is one of the powers of poetry, eh? Poetry helps us be open, to see and to feel the complexity in things that at first glance appear to be simple and self-apparent.

Oh, what an experience! The landscape & the people & the layers of stories about both! I’ve been trying to hold onto that openness and cognitive humility now that I’m back (not from Spain which is where I thought I was going, but from Cataluyna, where, humbly, I learned I was). Walking through the city with out-of-town visitors, including Julieanne & Fran, has helped, as they invite me to see the familiar with new eyes. And this post & your comments to Mary Lee has made me want to be more consciously aware of layers—the things within things within things. Thanks!

Thanks for reading, Vicki! I’ll bet it was fun to walk The City with new friends Julieanne and Fran (and Jan and Kim, too). I wished I could have been there. I love the Alice Munro quote (I think it was?) that you mentioned earlier (and that you reference here)…the thing within things. The more one looks, the more one sees. When I was a kid I remember watching clams on the bottom of the lake through the slats in the dock. A lot of people might not think that’s too exciting, but, well… 🙂