Photo Credit: Vinoth Chandar via Compfight

Favorite blogger, Vicki Vinton, posted recently about how, in a unit for 9th grade students, the New York State curriculum tamed the unruly wildness of Karen Russell’s short story, “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves” by caging it inside 130 text dependent questions, nearly 40 vocabulary words, 200+ pages of lesson plans, and a single interpretation.

In a follow-up comment, Vicki offered this lovely quote from Alice Munro to illustrate the complexity of thought that a bazillion text-dependent questions erases: “The complexity of things–the things with things–just seems to be endless. I mean nothing is easy, nothing is simple.” So true. And that’s why learning is so much fun.

Our school district recently purchased a reading series. Next week will be our first meeting to talk about what are our “expectations for fidelity.” I’m dreading that I will have to come clean that I’ve been cheating on it.

I admit that I feel completely incompetent when I look at the script for teaching the metacognitive strategies in our reading series. I wonder how I’m going to get the kids thinking by reading the script for each day. Furthermore, my brain is small and old. I can’t seem to remember what I have to do and say if that list extends beyond two things. I can’t imagine how daunting it would be to run kids through a mill like that described by Vicki…210 pages.

It’s not that I’m simply incompetent. I’m fine when there’s a conversation going on. I can even listen actively and closely! I remember what’s happening and my old brain makes connections between things pretty well. But I’m downright terrible when I’m trying to remember more than the point or two that will be our learning for the day. And if I can’t feel a certain joy, a touch of new-ness along with the complexity of a good conversation and some good ideas, I’m completely flummoxed.

* * * * * * * * *

Here’s part of the confession that I’m practicing for next week: I’m unfaithful. I sometimes spend too much time reading aloud to the kids. And that comes at the expense of spending time with “the program.”

We’ve just started reading Katherine Applegate’s The One and Only Ivan. It’s been fun. I’m struck by how much exploring the complexity of things, the “things with things” as Munro says, is facilitated by the simplicity of presentation. I can’t remember 130 questions, but I can remember one big question, and whole bunch of “What makes you think that?” questions to keep the conversation going and growing.

Reading Session 1: Who are these characters?

As usual, when we started Ivan we collected details, thoughts, and wonders about the book. Collecting these helped us notice concrete things about the characters and setting, helped us get to know Ivan and other characters, and it helped us form a “rough draft” about what might be happening in the story. (I learned how to do this kind of thinking from Vinton and Dorothy Barnhouse’s wonderful book, What Readers Really Do, though it also made a lot of sense to me just from life.)

My goal was to read, pause for the kids to notice details, allow them to generate provisional thoughts, and to state their initial questions. They took notes in their reading notebooks while I read. Periodically, we stopped to talk about what they were noticing. My role was to notice what they were saying, name it as a detail, thought, or wonder, and ask them to connect the three areas together so they could see how books create meaning.

For example, when someone thought Ivan was lonely in his cage, I’d ask — What makes you think that? — and we would examine the details the students provided. When someone brought up the mental picture Ivan had of his silverback father in the jungle beating his chest to protect the group, I’d ask: What do you think that means? What does that make you wonder about? (One thought: Maybe Ivan remembers a time when he was in the jungle with his family. And a wonder: I wonder if Ivan was somehow stolen from the jungle, or if his family was killed and he is an orphan?)

Reading Session 2: What does Ivan really want?

What do teachers do if they aren’t asking 130 questions to push children deeper into a story?

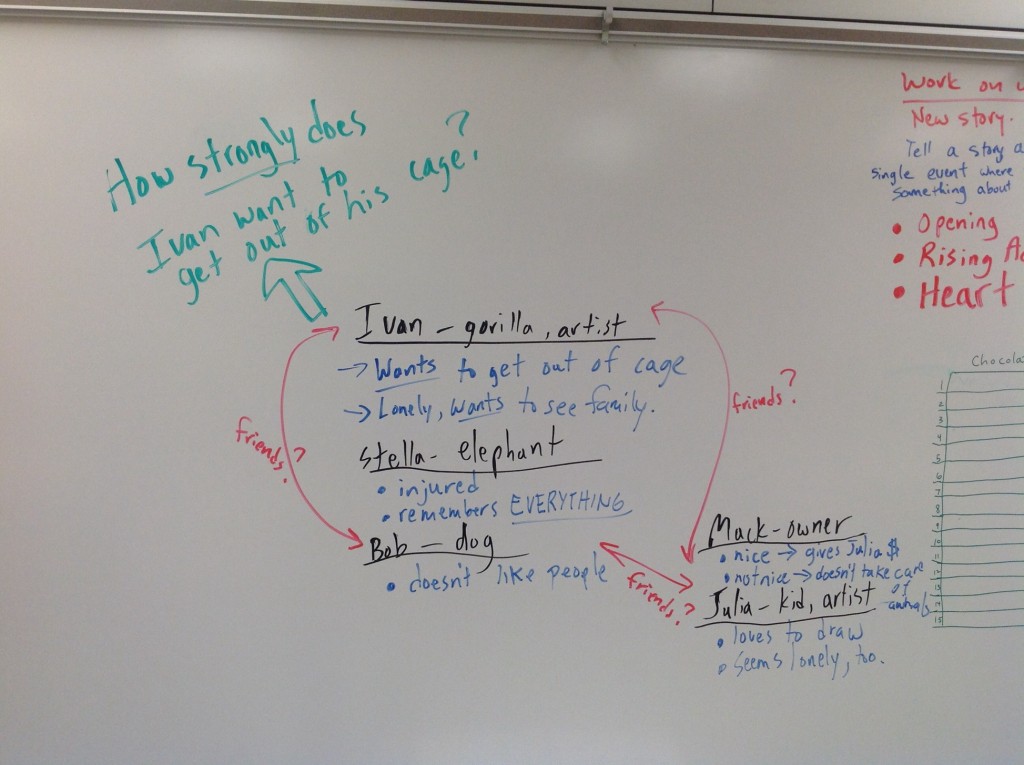

One big thing we can do is serve as a collector of ideas, to be the “working memory” in the class brain. Novice readers don’t have as much practice keeping the “stuff” of stories in their heads as do experts; they often don’t know how readers tell and re-tell the story to themselves as they are reading. So, prior to session 2, I sketched out on the white board what we had talked about in session 1. I figured this would provide a space for us to re-tell the story in an exploratory way. I asked the children to add in things that I forgot. Here’s a photo of that sketch:

We had done a lot of thinking about the characters in session 1. I told them it was a great sign that they knew so much about the characters and what they might be thinking and feeling; that is what readers really do.

My one big idea for this session was that I wanted them to develop a “rough draft” of the story. So I asked the children what they thought Ivan wanted, reminding them of the work we had done on story elements earlier in the year. Almost to a person, the children thought that Ivan wanted freedom, to bust out of the cage and be rejoined with this family. They imagined an almost Rambo-like escape! And they offered lots of evidence that this might be possible:

- the hole in the glass wall from the baseball bat could be enlarged;

- the sadness Ivan seemed to feel being locked up in the cage means he doesn’t like it and wants to escape;

- the way he didn’t really respect humans and how they acted might mean he is ready to take them on physically;

- the way he had little memories of the beauty of the jungle, and how pathetic the jungle “scene” looked on the wall of his domain showed his longing for that part of his long-gone life;

- the snippets of memories he had of his father, mother, and his dear sister, Tag, showed his longing, too.

The children even had an idea that Ivan would see a member of his family on the TV in his cage in some show that he watched, and that this would kindle in him a desire to break out. He’d go berserk and rip through the wall and somehow return to the wild. I was struck by how passionate the children felt about Ivan’s future escape.

Basically, all of this discussion came from my one question — What does Ivan really want? — and from what the kids were saying to each other. My job was to clear space for the conversation, ask kids to talk to each other by adding on, or disagreeing respectfully, and for the children to justify their ideas to each other and to themselves. (See an earlier post where I reflected on Peter Johnston’s idea that use of evidence flows from the desire to communicate, not from a mandate from the State.) From this discussion, we were able to find more details in the story that we hadn’t really brought to our consciousness earlier, and we created a more detailed and nuanced “re-telling” of the story. Did we find all of the important pieces of literary craft, pieces that 130 questions would undoubtedly lead us to “discover”? Probably not, but the ones we did find were pretty cool and useful.

And this all felt a lot like what I do when I read.

Reading Session 3: How strongly does Ivan want to escape?

Again, I organized the thinking from the previous session (reading session 2) on the whiteboard. Here’s a photo of what I wrote.

In this third session, I wanted the kids to consider the very thing they were so passionate about earlier — Ivan’s possible escape from his cage. I asked the kids this question: How strongly does Ivan want to escape from his cage? I asked them to slow down and consider it for awhile, trying to separate out what they would do if they were Ivan, from what they think Ivan would do. Evidence, please!

The first idea was Gabe’s. Surprisingly, he took on our dominant idea that Ivan would burst out of his cell in a blaze of glory. (Brave guy!) He thought Ivan didn’t seem like he wanted to leave his cage very much, which surprised him. After he explained, others agreed. They cited reasons like these:

- Ivan doesn’t get very mad. You’d have to be pretty mad to break out of a cage and take off from what you’d always known.

- Ivan seems to like to sit around and just watch TV and eat stuff.

- He seems depressed and unmotivated.

The next interpretation (Annika’s and Zach’s) built on Gabe’s. While they agreed that Ivan seemed kind of depressed and not able to break out of cage right now, they thought that would change sometime soon. Annika: “I think Stella is going to be important to the story, but we don’t know much about her yet. Maybe she’s going to talk to Ivan and help him change. She might help him see that he can leave. That will make him want to leave more and more until he can’t stand it anymore.”

A third interpretation came from Garrick and others who agreed that Ivan seemed depressed, but thought that he really wanted to break out of the cage, but was scared to try. When I pressed for more, he came up with this explanation: “Ivan might have been taken from his family when he was a kid. He has these memories of them. Maybe he’s scared to go looking for them because maybe they are dead and he doesn’t want to find that out.”

Dylan piped in with a comparison between Bob, the dog, and Ivan saying, “Maybe Ivan and Bob are alike? Bob lost his family when they got killed on the highway. Now he doesn’t really want to settle down. It’s like he’s scared to get close to anyone. He doesn’t like most people and tries to stay away from them. Maybe Ivan is feeling a little the same way because he lost his family, too. Maybe they both don’t want to get close to anything because they are afraid of how painful it will be to lose them.”

What is next?

We haven’t moved on from here yet, but I think the next focus will be a diagram of the three rough drafts of what The One and Only Ivan means. We’ll talk some about how we have revised our draft from “Ivan will bust out of the cage and find his family!” to now several possibilities. We’ll keep our eyes open for the relationship between Stella and Ivan, between Ivan and Bob, and we’ll look for whether Ivan is getting angrier about being put in his cage. These questions will help us as we read further in the story.

What did I learn?

I learned that one of the best things I can do is serve as the “working memory” for the collective brain of our classroom. A good role for me as a teacher is to

- help the students “chunk” material into meaningful chunks (“Here’s what we said we knew about Ivan.”);

- name what they are doing (“We’re creating a rough draft of what we think this story is about. That will help us as we read farther.”);

- ask open-ended, meaning-making questions (“How strongly does Ivan want to leave his cage?”);

- ask questions that get to the basis for an interpretation (“What makes you think that?);

- collect and map the evolving interpretation as it unfolds (“Okay. Here’s a map of what we’ve talked about so far. Readers try to keep this stuff in their heads, but since we are practicing that, I’ve mapped it out on the board. Am I missing anything?”).

This all takes time, and lots of thinking that isn’t caged in by a script, (e.g. “Now we are going to learn how to make inferences. Here’s how you do it…”)

Sorry about such a long entry. What do you think? Do you do things like this, too? Do you have to teach from a program? Do you struggle, like I do, with how to fit something like what has happened with our reading of Ivan into the structure of that program?

Yep. I teach 2nd grade and after reading “What Readers Really Do” I have to let them tell me about their thinking. I label their thinking, just like you do, so they can know the strategies, but they have to make the connections. Ok, sometimes it’s just one kid, sometimes I re-phrase their thinking to make sense, but a script would not be any better. And we do have a scripted program, with books they can’t read independently or with a partner. In 2nd grade we must do this together. So I am reading aloud and they are listening for the evidence that supports their ideas, feelings, predictions, etc. I will try the visual map that you do. “have I left anything out?”

Thanks so much for reading this blog and offering a comment!

Ouch…your situation sounds like it’s difficult. Books that are too hard for the kids to read. Ugh. My situation (so far) isn’t as bad as the one your describe; it sure hurts, though, to hear that kids are going through this stuff in other places.

It also sounds like you’ve developed a similar “methodology” to what I’ve stumbled upon. Cool. I thought of the visual map as a way to (maybe even literally) become the working memory for the class brain. After reading Dan Willingham’s book about teaching and cognition, I began to think about how my scaffolding maybe could be in the form of expanding the working memory space so the students could hold more in their heads at one time, rather than doing the thinking for them. I’m going to think more about the implications of the “working memory bottleneck” that he describes, and what that might mean for me as a teacher. To me, it fits well with what Vicki has been talking about. I especially like his advice: The one who does the thinking, does the learning, which fits really well with Vicki’s book.

At any rate, thanks for your ideas, and thanks a bunch for reading this post!

I’ve wondered how you were faring in this brave new world. And looking at the gorgeous thinking your kids are doing with Ivan–and the way they were able to revise their thinking because of the question you posed–I found myself wondering something else. I saw Penny Kittle present at NCTE last year and she shared some work she did with a school where the teachers wrote a rubric for administrators about what they should see in her classroom.

I guess I’m wondering if you (ideally with colleagues) created one that was aligned to the CC reading, speaking & listening standards, the powers that be might be able to better see the depth of the work you’re doing, since what you’ve shared here directly correlates–at least to me–to RL4.1-4 and 6.

And on the like minds think alike front, I’ve had that same George Eliot quote on the wall by my desk for years.

Vicki,

First off, thanks so much for stopping by to chat. I so much appreciate the effort and the ideas, and I really enjoy the conversation.

What an intriguing idea, this one about a classroom rubric. I’ll search to see if I can find some kind of a draft that came out of Kittle’s talk. I also have some ideas, too, now that you brought this idea to my mind… There are several of us who are chafing, including my colleague, Megan, who is one of the smartest, most with-it teachers I know though she’s only been at this gig for less than three years. We really believe strongly in not being door-closed, Lone Rangers, but believe just as strongly in the capacity of children and teachers to make something interesting and wonderful together. She’s swamped with school and MA program (there are also a couple like minded others with families and obligations) but I’ll bet, together, we can come up with something interesting and useful…Thanks for the idea.

Before IVAN, I didn’t know of the George Eliot quote. We read it as we started the book, of course. One of the children brought it back to our attention as evidence that Ivan, though older, might be in for some changes as the story progressed. She made me write it on the board. 🙂

More fun with IVAN today.

I ABSOLUTELY think that you and any others who are able to teach the CCSS so masterfully WITHOUT a script, should be allowed to continue with your brilliant teaching! And if you need EVIDENCE to prove that what you are doing produces thinkers more critical and engaged than any program could ever hope for, well…you’ve got it in this post.

You not only listen to your students, you really hear what they are saying and you don’t judge or nudge, but let them discover that their thinking needs to change. That’s so powerful.

Here’s what I think your confession should be: “I am unfaithful. I have not taught the program because I’ve been too busy teaching my students.”

Stay the course. Be strong. We’re cheering for you!

Mary Lee. Thank you so very much for reading this extremely long post. I know that you are swamped with your own work right now, so that makes your thoughts that much more important to me.

This switch-over to a reading program has been very difficult for me, more difficult than I imagined. I’m still trying to figure out why I can’t seem to just say, heck with it and do my own thing. I guess I do my own thing, but without the heck with it attitude. That part is really difficult for me. As a result, it wears on me…big time. And to see someone as good as Megan trying to be a force for good, too, is hard.

I love Vicki’s suggestion to create a rubric. That would be good for us as an opportunity for reflection and focus, but also as something that could be potentially useful for others.

Thanks for taking the time to read. I really appreciate your generosity.