I promised myself that I’d use this blog space to think through things that I’ve seen in the classroom. Here’s a post that emerges out of noticing the way readers are thinking as they move into more complicated texts.

Both deep and shallow thinking

I’ve been struck by how some kids can seem so brilliant during read aloud — they can come up with really deep and insightful comments and even base them on the details of the story — but they sometimes struggle to make such deep meaning on their own. What was causing them to think so deeply at some times, and more shallowly at other times?

I began to notice that some children missed key ideas as they read independently, or in small groups. As these students developed greater confidence and skills they were able to read the words in more complex text, but seemed to be missing some of the meaning of the words. The words seemed to exist without texture and nuance and, as a result, it was hard for them to pick out the details that were important. My sense from listening to them read, was that they were reading and thinking mostly on the literal level and, as a result, were missing the deeper layers of meaning in the story.

At the same time, I’ve been very happy with using reading aloud as a moment of meeting, conversation, and learning. I’ve seen that my reading aloud provided some scaffold that allowed them to catch the meaning and importance of words that they weren’t able to catch on their own yet. Perhaps my voice inflection and the pacing of my reading conveyed some of the layers of meaning behind the words on the page, something they were not yet able to do on their own. For example, they would sometimes cite as evidence for their ideas how the character sounds, as in: “the character sounds angry”, not putting it together that the character’s “sound” was created by me! This scaffold provided them what they needed to engage in more complicated text on quite a high level, a level they weren’t able to accomplish on their own.

In a sense, while my reading aloud was helping to model how stories sound, and it provided a scaffold for their thinking, it took away some of the responsibility they had for interpreting the layered meanings of the words, too. My mind was prioritizing and interpreting as I read, something they would have to do when they read on their own. Maybe I needed to remove the scaffold and find out what they could do.

Poetry: Diving below the surface

So, last week I conducted a little experiment in the classroom focused around figurative language and poetry. I figured that a dive into figurative language might be at least one way to practice making meaning through looking below the surface of the text. I introduced a Ted Kooser poem to the children and we talked about it. I videotaped the lesson and studied it to see what happened. Here’s what I discovered.

First, we read the poem together three or four times. I asked them to circle words that seemed important, surprising, or meaningful.

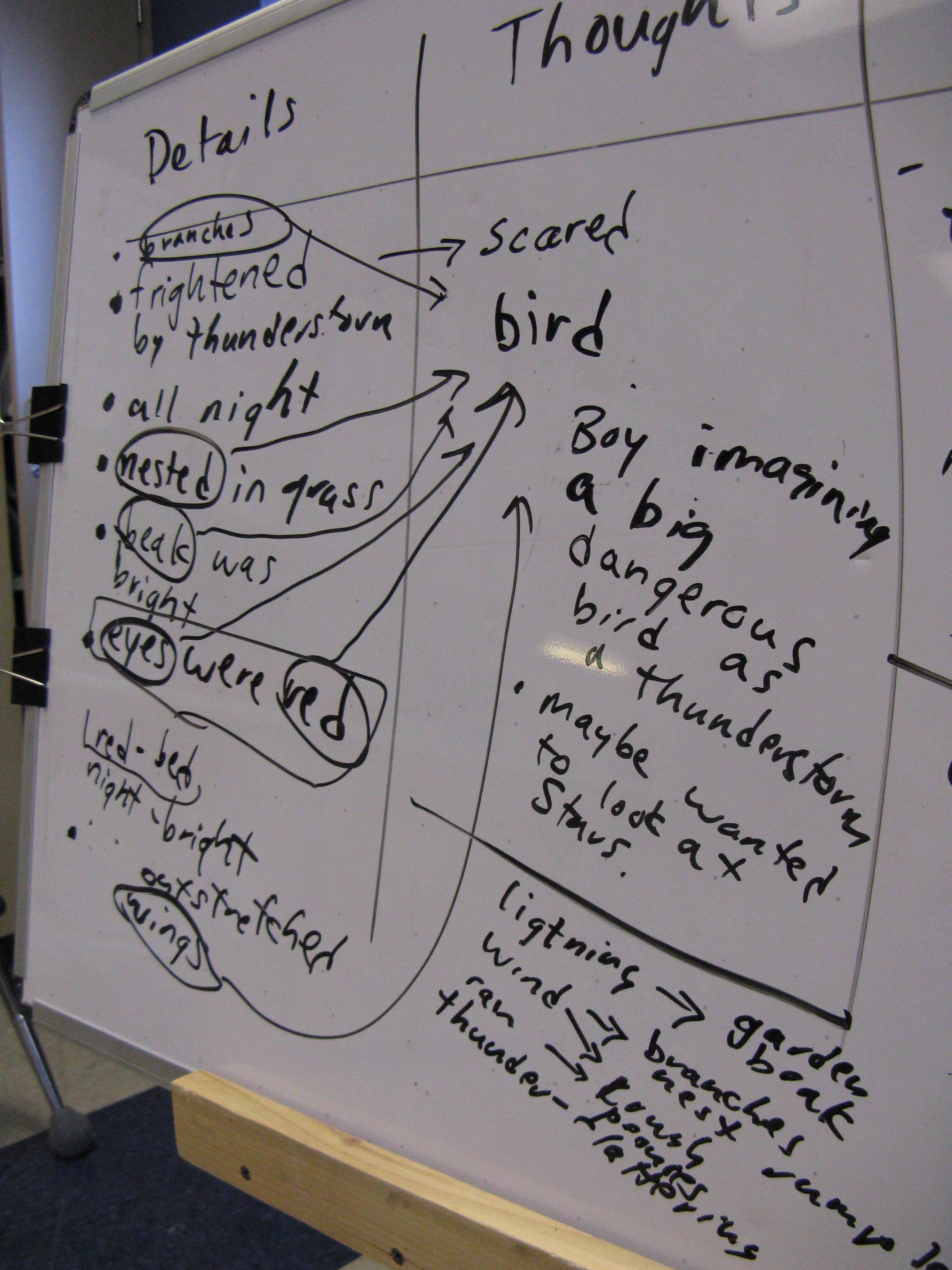

To keep a record of their thinking, I used a modified version a Know – Wonder chart from Vinton and Barnhouse; What Readers Really Do. I put in a middle section called “Thoughts” to separate out the details, and slow down the students down so as to keep them from jumping to conclusions. (This hack was based on the See, Think, Wonder routine from Making Thinking Visible.) I scribed (or scribbled, as my handwriting…welll…sucketh) what they said.

We first focused on noticing the details from the poem. You can see what they noticed listed in the detail section of the photo to the left. The video showed me trying to get them to linger on the details before they started drawing conclusions. I wanted us to use the time to go deeper into the details and look deeper into the text. I figured with a richer array of details, we could begin to use them to create thoughts and questions later in the process. This is the idea advanced in the See-Think-Wonder routine from Making Thinking Visible. Within a few minutes, the Detail side had much of its content.

Then we moved to develop thoughts and wonders from the details we had noticed. Looking at the details, a couple kids offered the idea that there seemed to be a lot about a bird in the poem, noticing words like “nested”, “beak”, “outstretched wings.” Soon, two related ideas emerged. First, one boy offered that the thunderstorm was kind of like a bird, but wasn’t exactly a bird. He explained that a thunderstorm can be big and scary like a giant bird, and that this poem might be comparing the two. Another boy agreed and said this poem described the storm like a bird was described in a book from the Beast Quest series. (Yes, these are third grade boys talking, and these are their literary references!)

I thought we might be onto something here. I was surprised by the way these two boys had gotten through the literal into the figurative fairly rapidly. Still, they hadn’t developed this idea much, but…rather than jump in, I waited.

The idea of a comparison sat there for a moment. Then, a third boy offered that the author might have seen a bird in the sky because he was looking up at a thunderstorm. Another chimed in that maybe the red eyes were the moon that he saw up in the sky as he was looking at the bird, which he saw when he looked up at the thunderstorm. His evidence was that branches are up high and so is the moon, so he might have been looking at one and seen the other. Another thought maybe the clouds of the storm looked like a bird because clouds can look like animals sometimes.

All these ideas seemed to reverse the quick move into exploring the figurative language surrounding the bird — thunderstorm metaphor. We were definitely back in the literal, and a quagmire up to our boot tops.

Finally, one boy said: “I disagree with both of you! This is about a thunderstorm!” He pointed us back to the title.

So I said, “What does a bird have to do with a thunderstorm? Like, what does a ‘sharp beak’ have to do with a thunderstorm? Let’s go back and read that line.” So we re-read:

…It’s beak was bright,

sharper than garden shears and, clattering,

it snipped bouquets of branches for its bed.

Suddenly, hands went up and kids offered suggestions:

“The beak is sharp, that’s like lightning!”

“Lightning can cut off branches like garden shears.”

And other revelations came:

“‘Rumpled grass.’ That must be the wind. Grass looks rumpled after a thunderstorm.”

“‘Outstretched wings crushed the peonies.’ That must be the wind, too. Wings make wind and blow everything around.”

“‘Clattering!’ That’s like thunder!”

“‘Snipped bouquets of branches for its bed.’ That’s the wind! A really strong thunderstorm breaks off branches. If you go outside after a really bad thunderstorm there are sometimes branches on the ground.”

Soon most kids were offering ways that the thunderstorm was like a big, scary bird. Finally, the kids tried to figure out what “The thunder’s eyes were red.” meant. By this time most were willing to entertain the idea that it might be more than something literally red. The remaining Literalists thought it might be lightning in the clouds as the storm went away. (Interesting…I thought to myself!) The New-Figuratives thought that the “red eyes” were supposed to make you feel scared of the storm because “red eyes” are often a sign of evil in movies and stories.

We left it as a mystery. I asked them how it would change the meaning of the poem if it was a storm moving away v. a sign of evil. They decided that it would be slightly less scary if the storm was moving away. I told them that they would have to decide for themselves whether the author wanted them to feel scared throughout the whole poem, or if the author wanted them to get a sense of the danger being over. Either way, though, they could prove what they were thinking by showing exactly what the author said.

What I learned

What did I learn from this 21 minute activity? Here’s a partial list:

1. Hold back and don’t talk. I learned a lot about how the kids thought when the initial figurative interpretation wasn’t taken up by other kids. I learned that it wasn’t persuasive, that they felt the need to search for literal meanings first.

2. Keep track of who says what. Watching the video really helped me see some of the suggestions offered by the kids. I had a general sense of where some kids were at from experiencing it, but watching the video helped me identify some kids who were having a really difficult time moving out of the literal and into the figurative. These kids are also some of the ones that have the hardest time catching some of the important parts in more books with more complex writing.

3. I think I’m right about how some are missing layers of meaning. As I listened to the explanations of what the poem might mean, I saw how some children picked up quickly on how Kooser might be using words in one way to mean something else. The kids all got a sense of the poem being scary, but I think that was because of the way I read it. Almost everyone could identify details that seemed important (and they picked good ones!), but moving from that to interpretation required them to leave the literal and move into the figurative. That was hard for some kids.

4. Struggle is good. I think a lot of kids came through this with a greater sense of how language can mean something different than at first glance. I could have told them that, but they wouldn’t have struggled with it. In fact, two of their classmates actually did tell them that early on in the conversation, but the idea was rejected for more concrete ideas. I think they just had to work through it themselves!

5. Going back to the text at some point helps ground the students. A key moment came when we went back into the text to see how a “beak” could be connected to a thunderstorm. Once they had the question in their minds (and could hear the question because they had struggled with it for awhile), then the figurative nature of the words emerged quickly and convincingly.

Next steps

Already this week I am working in a small group with some of the kids that had a harder time reading past the literal meaning of the words. I’ve chosen a fiction story (The Blue Ghost) that I know to be relatively easy to read, word-wise, but more difficult to read (meaning-wise) because so much is conveyed implicitly. I may post later on what I’ve discovered about how they are processing that text.

Also, I’ve read another poem, dog by Valerie Worth, to give them more practice with figurative language and how even concrete details can convey meanings that aren’t overtly “symbolic.” That would be a fun post, too, come to think of it.

Finally, this helped me see how sitting back and listening can help uncover how the kids are thinking. Using those data — which are oh-so-much more fun and powerful than the standardized test data, or even the IRI data — I’m able to address some fundamental issues that impede the meaning-making of the children who are struggling. I’m excited to see where this takes me. In short, listening carefully to the kids try to puzzle stuff out helps me understand the kids, and helps them be receptive to the help.

UPDATE

As I finished writing this post, another fantastic post from Vicki Vinton arrived in my inbox. The subject of her post, I believe, is very similar to the puzzle that I’m facing in my classroom. She explores how meaning-making breaks down for one girl while reading a “good fit” book, and how long, deep conversation helped her uncover the issue. As usual, she is articulate and artful and insightful. Read it.

Steve, I found your analysis very insightful and believe I will be able to put it to good use in my own Grade Three classroom this year. My head spun as I realized that for all my fabulous read-alouds to the class where I modelled reading and thinking, I have perhaps not given them as much opportunity to think for themselves after reading themselves – thanks for the jog!

I reckon I will have a better chance of reviewing a lesson if I do an audio recording rather than a video recording. I can then review it on my home commute.

Your blog has been a pleasure to discover.

Cheers

Brette

@brettelockyer

Hi, Brette!

A fellow third grade teacher. (Right??) And an Aussie to boot. Wow! Great to meet you. (My brother regularly goes to Australia and comes back with many wonderful stories, and an immense love for the country and folks he’s met there.)

I’ve also been super proud of my read alouds. (I still am, and LOVE to do them. They are probably the primary way I model and get the kids started thinking.) But I realized that I my reading aloud was also a kind of scaffold for the kids, so I needed to deal with that realization.

As I watched the video (I’ve also recorded audio, ’cause it’s easier for me, too), I realized that I was getting all sorts of information that I could put together with other stuff that I had noticed, but hadn’t really processed in my mind. The re-grouping came out of the connections I made between those previous moments, and by keeping quiet, listening, and asking for clarification during the read aloud around the poem. As you begin your year, it would be fun to hear what you are doing and how you are thinking your way through puzzles.

Great to meet you!

All the best,

steve

Pingback: Sorting through details: Notes on a couple transitional readers | inside the dog…

Pingback: Re-reading to discover author choices — more notes on transitional readers | inside the dog…

Pingback: Re-reading to discover author choices — more notes on transitional readers

Pingback: Sorting through details: Notes on a couple transitional readers